The decree of 2 January 1793 stipulated that the year II of the Republic began on 1 January 1793. This usage was modified on 22 September 1792 when the Republic was proclaimed and the Convention decided that all public documents would be dated Year I of the French Republic. After some hesitation the assembly decided on 2 January 1792 that all official documents would use the "era of Liberty" and that the year IV of Liberty started on 1 January 1792. Originally, the choice of epoch was either 1 January 1789 or 14 July 1789. It was in 1792, with the practical problem of dating financial transactions, that the legislative assembly was confronted with the problem of the calendar. Immediately following 14 July 1789, papers and pamphlets started calling 1789 year I of Liberty and the following years II and III. Indeed, there was initially a debate as to whether the calendar should celebrate the Revolution, i.e., 1789, or the Republic, i.e., 1792.

The name "French Revolutionary Calendar" refers to the fact that the calendar was created during the Revolution, but is somewhat of a misnomer. It is because of his position as rapporteur of the commission that the creation of the republican calendar is attributed to Romme. As the rapporteur of the commission, Charles-Gilbert Romme presented the new calendar to the Jacobin-controlled National Convention on 23 September 1793, which adopted it on 24 October 1793 and also extended it proleptically to its epoch of 22 September 1792. They associated with their work the chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, the mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the astronomer Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande, the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the astronomer and naval geographer Alexandre Guy Pingré, and the poet, actor and playwright Fabre d'Églantine, who invented the names of the months, with the help of André Thouin, gardener at the Jardin des Plantes of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris. The new calendar was created by a commission under the direction of the politician Charles Gilbert Romme seconded by Claude Joseph Ferry and Charles-François Dupuis. Natural constants, multiples of ten, and Latin derivations formed the fundamental blocks from which the new systems were built. Amid nostalgia for the ancient Roman Republic, the theories of the Enlightenment were at their peak, and the devisors of the new systems looked to nature for their inspiration.

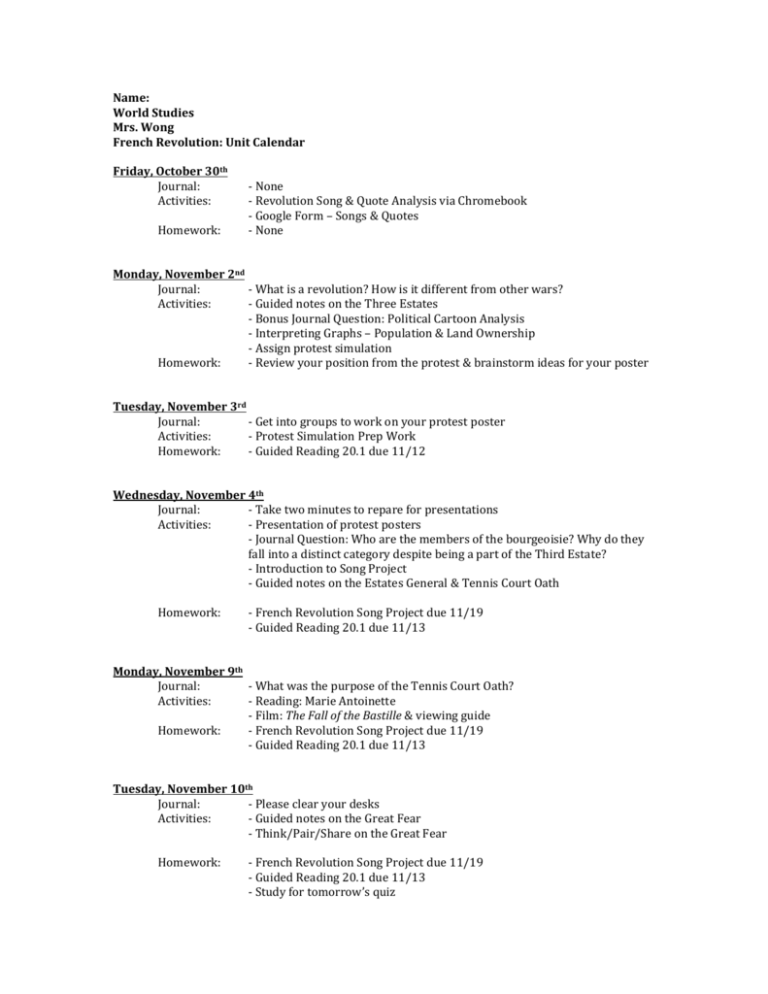

The new Republican government sought to institute, among other reforms, a new social and legal system, a new system of weights and measures (which became the metric system), and a new calendar. The days of the French Revolution and Republic saw many efforts to sweep away various trappings of the ancien régime some of these were more successful than others. A copy of the French Republican Calendar in the Historical Museum of Lausanne.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)